“Please, come and look.”

It was a hazy Wednesday afternoon up in the hills east of Accra, and I was being summoned. We had arrived just a few minutes earlier at the Aburi Market, where we were tasked with both purchasing handmade wooden items and, more importantly, learning the art of bartering.

I’m from the United States. The closest thing to bartering there is eyeing a restaurant menu and asking, “Really? 11 dollars for a hamburger?” At least in my own personal experience, I’ve never demanded that someone lower a price of a good when I lack any knowledge of its true value.

Apparently, things are different in Ghana. Which, of course, brings us back to that gentle call from an elderly woodcarver.

“Please, come and look.”

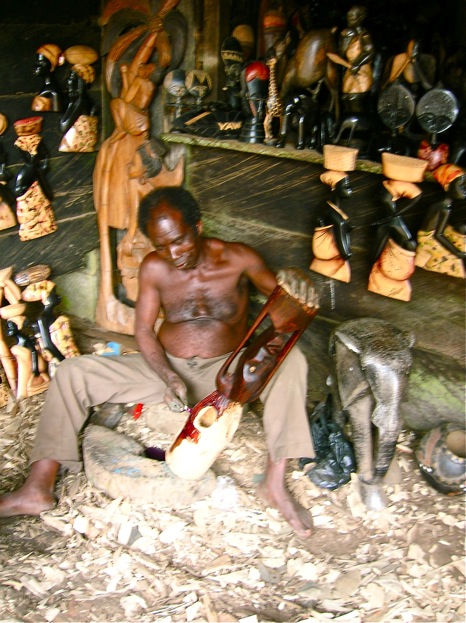

I was passing by his stand, just one in a line of about thirty that stretched across both sides of the highway. He was sitting on the ground, and much calmer than the other sellers (many of whom practically grabbed you and shoved you inside). In front of him was a half-finished sculpture that was slowly beginning to take shape. He and I were the only ones there.

After he called me, I slowly made my way through the entrance. Somehow, on account of what I would guess to be a nasty concoction of First Time Barterer Syndrome (yes, that’s real), lack of confidence in a foreign country, and my own general awkwardness, I managed to not say a single word as I walked in.

No “Hello.” No “How are you?” Not even a cheesy American wave. The man stared at me, halfway grinning as if he could sense my discomfort. After my utter failure in the realm of politeness, he took it upon himself to break the ice.

“I’m doing fine,” he said.

I took it as a subtle, friendly way of saying, “It looks like you forgot your manners back in the U.S.”

Now I was supposed to barter with this man? After I already insulted him? This experience couldn’t have been off to a worse start. After a quick glance at his work (which was beautiful), I cut my losses and shuffled off to the next stand.

Thankfully, not all of my visits went so poorly. I successfully functioned as a human being and greeted the other storekeepers, and even broke out a bit of Twi in hopes of impressing them and showing that I’m trying. But there was still bartering to do, and that never got any easier.

On the surface, it seems simple. As our guide Sonny told us, find out what the asking price is and then offer about one-third of it to kick things off. In theory, you should end up walking away with an item at about half price.

But it’s one thing to say it, and a whole other monster to hear the offers coming out of your mouth. With one item (a Ghanaian “unity stand” with a globe on top of it), the seller asked for 30 cidi (around 20 American dollars). I countered with an offer of 15 (which is actually higher than what was suggested), and his face immediately dropped.

He explained that the craft was handmade, and my offer just wasn’t acceptable. I feebly persisted, and then upped the offer to 17 cidi. He moved down to 25, and we settled at 21.

I had similar experiences at other stores, eventually coming away with four items. The prices were each whittled down in some way or another, and I even won a battle with the infamous “turn and walk away strategy.” When my price was refused for a map of Africa, I began my exit before I was immediately stopped and acquiesced.

So yes, I won a few battles with the merchants. But in the end, as the bus drove down from the hills and back toward Accra, I was left with a hollow feeling. Really, what difference did it make to me whether a wooden rhinoceros cost 15 or 20 cidi? Five cidi likely meant 1,000 times more to the artists than it did to me.

Sitting next to me, Professor Jim Earl put it best.

“There is no glory in getting something dirt cheap,” he said. “When you’re buying it from someone who is dirt poor.”

Patrick, I am enjoying your blog. What a wonderful experience you are having. Are you hot all the time? Do the bugs bother you when you are sleeping?

Hi Patrick,

“First Time Barterer Syndrome” Ha! Ha! Too funny! I’m always too uncomfortable to barter, I guess I tend to agree with Professor Jim Earl, but Jolene’s Dad is the best I’ve ever seen. The “turn and walk away” plan is always effective. I’m glad you are getting the hang of it and I hope you have been able to buy wonderful pieces that you will treasure forever! You’ll never regret spending every cidi you have on gifts for yourself, but you’ll always wish you could go back and buy that one item that you loved.

Peace, Love & Joy,

Joyce